Key details

Date

- 20 September 2021

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 4 minutes

The Wood Street Altarpiece is a public artwork designed by RCA alumna Eleanor Hill. Installed in the underpass of a railway bridge next to Wood Street Station in Walthamstow, east London, the screen-printed enamel triptych celebrates significant local places and stories gathered from the community.

Key details

Date

- 20 September 2021

Author

- RCA

Read time

- 4 minutes

The commission was the result of an open call run by Making Places for Waltham Forest Council, in partnership with Create London. It provided Hill with the opportunity to put into practice methods and techniques she developed at the RCA, which centre around engaging communities in sharing local knowledge.

What are the narratives explored through the altarpiece?

The piece tells the story of three realms of ecological life expressed by the community in Walthamstow and contemporary London: the woods of Epping Forest, the urban streets around Wood Street, and the private gardens of the domestic home. It contains portraits of individuals who live in the area, who have contributed to the ecology and improved their local environment.

The central panel of The Gardens of Wood Street depicts several members of local gardening club Wood Street South Gardening Club who, last October, planted 5,000 spring bulbs in the pouring rain. They are one of the four community groups in the local area who have worked tirelessly to bring planting to shared spaces, maintain and establish allotments, playgrounds and bring people together to dig, water and harvest.

The south-east border of Epping Forest, London’s largest open space, crosses through Wood Street. The left panel depicts the multi-species relationships and activities which take place in the woods. St. Peter’s Church is shown here flooded with the yellow Sickle-Leaved Hare’s-Ear flower. This plant, which is on the brink of extinction, was discovered in the forest and is thought to be the only surviving colony in Britain. This site has been used to collect and disseminate seeds to other sites across the UK.

How did the natural environment emerge as the focus for the work?

There is a thriving network of gardeners and community-managed green spaces in the area. I went gardening and met with the local gardeners who were working together to improve their local environment. I also asked the wider community to participate in the project by sharing an image and short piece of text which reflected or celebrated their local green space. These were shared with the community through an Instagram account.

The entries covered a range of ecological occurrences, such as specific species of plants, their meaning and significance culturally and personally. Many posts reflected the role that plants play in healing trauma caused by the pandemic, coping with grief, loss and personal struggles.

This has been an amazing opportunity to reflect on the importance of nature in a piece which unites the community set in the public space.

How did you develop this approach to socially engaged practice?

My architectural work has been led by a social engagement process rather than design-led principles. This has roots in my own personal sense of responsibility for the environment, and the people and creatures we share it with. But the relationship to my working process came out of understanding the inequality and poverty of space across society.

“I focused my work at the RCA on a radically social practice – one which was community-led rather than profit led.”

Training to be an architect confronts you with a lot of pressing social and environmental issues, particularly around housing and basic needs for shelter and open space. It’s a very tricky field to intervene in, balancing urban pressures with societal pressures. Often I found that I was compromising values in face of practical or budgetary hard-lines. This is why I focused my work at the RCA on a radically social practice – one which was community-led, rather than profit-led.

In what ways did the Architecture MA at the RCA support this way of working?

Studying at the RCA was critical to developing this process. My studio tutors (Diana Ibáñez López and Dr David Knight) supported and shaped these thoughts from the outset and continue to inform my work today. They provided opportunities for us to engage our academic work alongside broader cultural and political trends, paying close attention to the governing forces which shape our cities and communities.

“Studying at the RCA allowed me to work on my own ideas developing my own approach to architecture and design.”

Studying at the RCA allowed me to work on my own ideas, developing my own approach to architecture and design. It was actively encouraged to develop your own unique processes, often with an experimental, multidisciplinary approach formed by being situated among art students. It is an environment which really prepares you to situate your work as a real practice, many of my peers are working on their own projects which were conceived at the RCA.

What was the focus of your studies at the RCA?

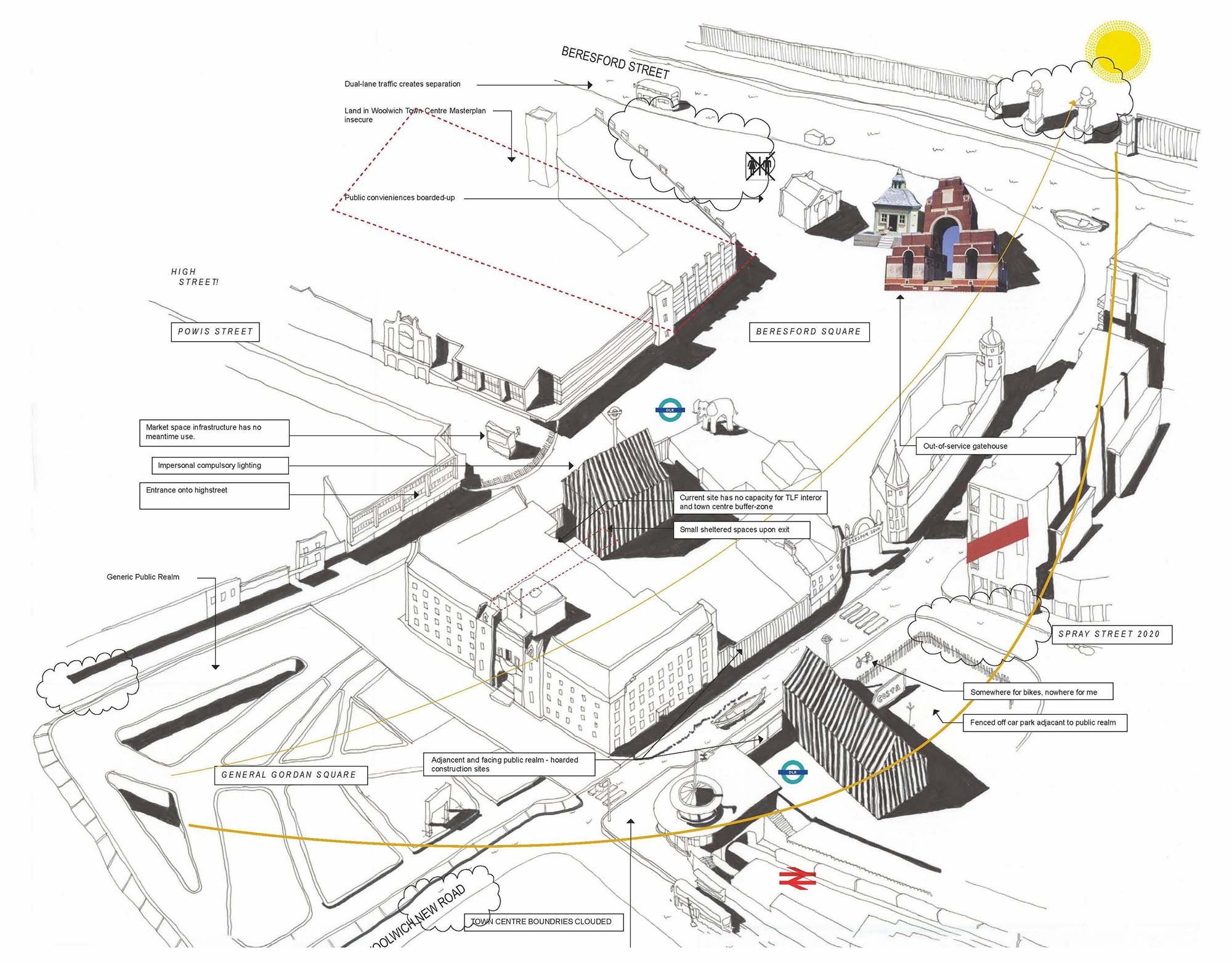

I focused on inclusivity and access to urban planning, taking a critical stance against the increasing privatisation of public space and public services in the UK. I designed a project with the input from market traders in Woolwich for a new indoor market and public space which was broadly engaged in community wealth building and entrepreneurialism. After this I was approached for a commission from a local campaign group who were attempting to save the borough’s public archive from closure during the waterfront regeneration project.

I also worked as an artist for a development cooperation, running a consultation workshop for Old Oak Common and Park Royal Development Cooperation, being the mediator between the urban planners and the community. I took this approach throughout my education, focusing on blurring the boundary between campaigner and designer, advocating for a community's needs.

What do you have planned next?

During a residency in Denmark, I collaborated with friend and designer James Powell on a series of landscape sculptures concerned with access and boundaries within rural communities. This has opened a new line of inquiry for me on rural environments and communities, particularly around rights of way and access to land – something which is vastly challenged by laws and restrictions on the side of powerful and wealthy private landowners. In light of the coronavirus pandemic and the project at Wood Street, I collected stories which spoke of the growing need for ecological accessibility. Ecological-poverty is something I would like to continue addressing through design, education and through art.