Key details

Date

- 14 February 2022

Author

- Lisa Pierre

Read time

- 19 minutes

Michela Magas (MA Communication Design, 1994) bridges the worlds of science and art, design and technology, and academic research and industry, with a track record of over 25 years of innovation. She is Innovation Advisor to the European Commission and the G7 leaders, creator of the Industry Commons and Member of President von der Leyen's High Level Round Table for the New European Bauhaus. She sits on the Advisory Board of CERN IdeaSquare – the CERN space for frontier innovation (ISAB-G).

In 2017 she was awarded European Woman Innovator of the Year and in 2016 she was presented with an Innovation Luminary Award for Creative Innovation. In 2019 the Leonardo Journal, by the International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology published by MIT Press, recognised her as an Outstanding Peer Reviewer.

Why do you think design brings people together?

For me, the one takeaway from working with amazing people at the RCA was the idea that I could use design to create a space for common understanding where we can involve different domains and areas of knowledge in design processes and translate ideas into practice through collaborative prototyping. Inviting other disciplines to collaborate has been used in design education, but this method of working is very rare in other domains. In design, we emerge from each collective cross-domain experience with a renewed understanding of the affordances, methods of expression, and the jointly created knowledge. Places where connections can happen or where disparate domains collide are beautiful and fertile places for people to grow. This is important for public spaces, environments, services or communications – but also for the design of supporting systems and technologies.

When we were asked by the G7 leaders how should they use digital technology to communicate with citizens, my suggestion was that they should consider digitally-connected bicycle sharing schemes or data enabled cultural heritage and public buildings as an interface and a place where they can connect to people. So my approach to design is inherently pluralistic and embraces all kinds of abilities and knowledge from multiple disciplines. This helps to create spaces that accommodate multiple perspectives. It is one of the reasons why design is an integral part of a high-level initiative such as the New European Bauhaus: a space for common understanding answers all three ambitions of the NEB initiative - it is sustainable, inclusive and a beautiful place.

A lot of what you do is driven by a focus on bringing people together to make deliberate decisions that enable long-term creativity, innovation, research and reveal new human possibilities. Do you think that collaboration is essential to innovation?

Critique of decision-making systems is very common in art and design, but good system design that has the courage to propose new value systems is rare. There is an assumption that system design is inherently top-down, prone to abuse, and will ultimately lead to injustice for some, if not many. And yet design, as a rigorous discipline, has all the ingredients for creating better social conditions, and when it is employed for that purpose, it cuts across other domains, becoming a major horizontal enabler and facilitator for people to benefit from each other’s contributions – since this is what society is for (or should be). Critiquing, compartmentalising, focusing on relatively small well-formulated injections – this is wise and safe in environments with finite access to knowledge, but for broader impacts, it is important to learn how to join forces with people from other knowledge domains and bridge various modes of expression. Intelligent cooperation is a phenomenal strategic skill and the heart of civilised coexistence.

So what really matters in collaborative environments is that we don't cancel each other out. Often when we talk about the innovation potential of hybridity, there is a misconception that it's enough to take various ingredients and throw them into a big pot. A big mashup is not good in its own right. What is important is that we cultivate the knowledge areas that contribute value to this common pool and encourage them all to grow, creating a space where we can respect and get inspired by each other. For a discipline, it's helpful to have a cross-check in another domain to ensure meaningful application of their knowledge. Each knowledge domain creates its own culture, develops its own language and its own methodologies. If you can understand the other's perspective, your eyes open up to different possibilities. Valuable breakthroughs happen when we reach that level of understanding.

You have developed programmes and courses for a number of Institutions – including the Royal College of Art. What kind of skills do people need for navigating our changing world?

Designers often underestimate what their training has given them or enabled them to do. Traditionally the scientific community methods of deduction and induction, which lead to a conclusion, seemed highly rational as methods, while the designer's brain training was perceived as far more chaotic, opening up too many possibilities. Their decision-making process was often framed as irrational or perhaps too reliant upon some kind of instinct. Many designers will tell you that they observe phenomena 24/7 because they are trained to do so, and that gives them the ability to join the dots between seemingly disparate phenomena. But what is generally underestimated is the value of this approach as a rigorous methodology for generating new knowledge, especially when compared to the linear and systematic scientific rigour.

The value of the design methodology becomes really clear when we prototype digitally-enabled products and systems that use frontier technologies such as AI, deep learning and neural nets. These keep throwing surprising results and can be overwhelming for linear thinkers who rely on prior art to deduce the outcomes or induce results using statistical probability. No linear problem-solving system can prepare you for the unknown unknowns that these systems throw up unless you have been trained to do problem-solving by questioning the subject matter from completely different perspectives and are comfortable dealing with surprising scenarios. Design equips us with non-routine cognitive skills, which are essential for original and often breakthrough insights in these environments.

You say the way forward for career paths is nonlinear and nonrepetitive. When you graduated from the RCA you worked on the global expansion of the Financial Times and you are now doing something very different. What twists and turns on your path changed your direction?

I graduated from the RCA in 1994 with a concept that created a new system for a newspaper in the digital age. The country I came from was at war, and the public perception of it was based on extracting meaning from the erratic news delivery. In terms of presentation, it was the classic McLuhan scenario – the approach to the new medium had been inherited from a century of practice and fitted awkwardly within the new system, which offered a dynamic environment with potential for agile interactions with the content. So the ergonomics of how you interacted with the newspaper as an object on public transport were as important as how the information reached you and in which order, as well as how it was assembled, how the news desk was organised and how people sat together and made those decisions. I was headhunted by the FT during the RCA Pre-Private View and landed a position the following Monday. The FT expansion involved a great deal of system design that innovated with the new digital affordances, and I was put immediately in charge of a new section.

Already in the 1990s at the FT, we were working on a daily basis with what we now refer to as big data. How meaning was extracted from this big data influenced a lot of decision-makers. I kept thinking that there were better ways to manage the flood of data which was literally now pouring on us from the incoming news streams. It was flowing in chronological order, but it was thematically unmanageable. It posed a challenge similar to the one presented by recent outputs from neural networks: how to ensure meaningful and responsible outcomes.

I started to think of better ways to organise data but was not allowed to move to the digital edition – I was told that I was too valuable on the news floor. So I decided to lock myself in the studio, which I founded with my RCA partner Peter Russell-Clarke (who later joined Jony Ive on the design of the first iPhone) and teach myself how to programme a digital system that could handle data in agile ways. The new system I wrote won me commissions from internationals and got me headhunted by Apple. I had written a dynamic system that allowed virtual 3D browsing of large data and media files seamlessly for the user by anticipating their download needs. This was 2003, and everything south of Paris was still running on 56K modems. When I was brought to Cupertino, the system received a lot of attention – it was the precursor of what later became Apple’s Coverflow.

This focus on the design of systems and how to extract meaning from them, understanding of affordances and opportunities, enablers and incentives, is a solid thread throughout my work. It led to a patent for identifying the smallest cultural unit of music, a system for supporting the creation and tracking of intellectual property for collaborative innovator communities, and the design of innovation ecosystems for the European Commission – all by being initially headhunted to join research teams. The EU headhunted me to join their programmes in 2010 after awarding me with their first “art meets science” award. Industry Commons, which is now a major track in the European Commission’s funding programme, is the culmination of all previous experience of designing systems – it is a concept for a system for cross-domain industrial data interoperability, which creates a level playing field for both innovator communities and global industrial partners, and has major implications on how we extract value from collaboration.

There is, however, one major twist in this tale. I never thought I would end up in policymaking. But as soon as I was headhunted to join the EU research and innovation programmes, I was asked to join industry advisory groups, and I began simply by feeding knowledge from grassroots community innovation and design experimentation to policy. I thought to myself – I'll do policy for as long as they'll listen and as long as I can see the resulting benefits coming back to the communities of practice. My policymaking colleagues’ attention to what I had to bring to the table grew and became quite surprising. I can now safely say that there is evidence of best practice from our prototyping being implemented right across the EU programmes.

You are the founder of MTF (Music Tech Fest) Labs, a global community platform of over 7,500 creative innovators and scientific researchers. The platform provides a test case for innovation in areas as diverse as neuroscience, forestry and microcomputing. Tell us why you decided to set this up and how has it grown since your original concept?

At the heart of founding MTF 10 years ago was the idea of making new technological affordances available to designers and creators, and allowing the authors of frontier technologies to be involved in technology transfer to new and exciting cultural expressions and emerging market applications. To do this, I needed to gather scientific researchers, industry engineers, artists, designers, makers, hackers, entrepreneurs, all in the same space, and create a level playing field - something traditionally perceived as extremely difficult because of the variety of languages and parameters involved.From experience of authoring programmes with the RCA Design Products and Goldsmiths Design Critical Practice, as well as programming discovery systems for Peter Gabriel's music data initiatives and directing a European music tech roadmap, it was clear to me that a few elements had to come together. Everyone had to join in a creative setting and have the opportunity to express their knowledge in new ways. The setting had to be physical, based on design methods of translating thought into practice and collaborative prototyping. It had to be supported by cutting edge technology research, electronics and data connectivity transferred to the physical space, where a performance allowed for new modes of expression to be experienced by everyone in the room. It had to be underpinned by ethical principles that create a level playing field.

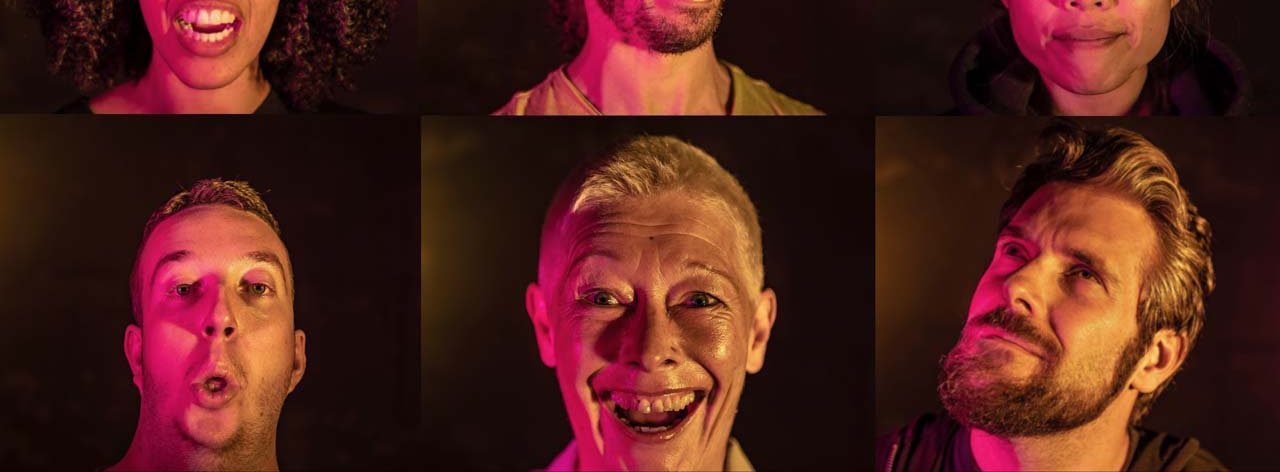

At the centre of all activities, music was our social glue. Music is a universal language and perhaps the most agile of methods of expression. So we got our hands dirty with prototyping and discovery of new ways in which we could do things together with music at the centre, joining all of the knowledge from brilliant minds in the room. We framed that agile, music-enabled space with questions of ethics and empathy, mischief and responsibility, sometimes with playful interventions, provocations and at other times by pushing at the edges of what we can be as humans.

How can we stop thinking about people as “normal” and create conditions for everyone to be extraordinary? How can we shift perceptions of who are the people we can all aspire to and why? When in 2016 MTF grew to over 5000 contributors, I engaged bionic artist and fearless advocate of experimentation with frontier technologies, Viktoria Modesta, to be at the centre of shifting paradigms and reframing our notions of ability.We soon realised that we had jointly discovered some phenomenal new affordances provided by the new systems that we were building. These were moments of revelation. I always compare this to the fact that before someone invented the piano, you couldn't have had a pianist virtuoso - the idea and the affordance didn't exist. You can't have a racing driver champion if you don't develop a racing car. It seems so simple, but we keep forgetting this when we build new technologies.

Experiments we've done with, for instance, a blind singer and vocal coach from the Sibelius Academy Riikka Hänninen, who proved to be incredibly talented with brain-computer interfaces, worked because we actually built a system that allowed her to express herself extremely efficiently in new ways. She was able to play music directly from her brain instantly, on the first try, while others took 2 hours to train to do the same. Someone who in the “mechanical era” was labelled as “disabled” because she could not identify the levers to interact with was now, in the era of brain-computer interfaces, far more talented than the rest of us.I placed at the forefront this idea that what one is, or can be, is constantly evolving: Imogen Heap as a blockchain and rights activist, Robyn as a children’s education reformer, world-renown professor of AI and robotics Danica Kragic as a fashion designer and maker, BBC Click presenter LJ Rich as a hacker and synaesthete, Member of European Parliament and ex news broadcaster Eva Kaili as a campaigner for the union of science, technology and the arts. By shifting perceptions of what drives people and why, during our mass-scale prototyping events, from over 800 participants, we managed to achieve 53% participation in technology prototyping by those who declared themselves female.

So when we set up the paradigm-shifting questions, build systems and test them, we discover that perhaps some things work better, or they work better for certain people, or that we need to take another direction because we have uncovered new potential or new affordances. This is classic design methodology, except that the number of revelations and surprises is increased by pouring in all the knowledge from the brilliant minds in the room from various disciplines and the latest technological breakthroughs. I have been feeding such discoveries directly into high-level policy because they have major implications for our understanding of systems, interactions, communications or the future of work. Creating a transgenerational level playing field for live experimentation on the ground shows how you can break down cultural, social, knowledge and age barriers. Proving that we can swing the balance of participation in engineering, technology or politics to those who might have previously felt excluded provides a channel for policymakers to notice the importance of multiple and varied perspectives, and means we need to reframe our notions of ability, how we define the nature of work, or how we set up supporting systems.

Brick by brick, MTF has been reframing the culture of collaborative innovation, turning creators into early adopters of frontier technologies and positioning itself close to emerging markets and cultural movements. The value of this space was quickly picked up by industry: first the indie music labels and digital platforms, then the major labels and major tech companies, then lighting, automotive, space and primary industries. We directly influenced the digital transformation of the music industry and pre-empted the paradigm shift for all other industries. This prompted me to design #MusicBricks and Industry Commons - both are systems of enablers that grew out of MTF testbeds.

Tell us about your involvement with #MusicBricks (and Industry Commons)?

I wrote #MusicBricks in 2014 in response to observing what was needed on the ground by grassroots innovation communities. I created an agile technology transfer methodology with technology transfer toolkits which were used like modular components similar to Lego Bricks for a variety of hybrid products and business models and piloted new ways of tracking intellectual property in collaborative environments (something we are now scaling for the EU Innovation Space). #MusicBricks ended up feeding 74% of the innovation recommendations by the Connect Advisory Forum to the EU Horizon Programme and resulted in a huge online following, multiple awards and funding streams.

During our pilots, industry kept coming to us and offering their IP to be embedded within our innovation toolkit. I realised that we were onto something that has been evolving since the music industry crashed with the advent of Napster in 1999: all industries were becoming data-driven, and all now required agile systems and creative solutions that can optimise and valorise the junctions between various capabilities where data and tangibles collide. I scaled this idea into the Industry Commons – an opportunity to generate new value for communities and businesses by building a system that creates a level playing field for cross-domain collaboration and trade while embedding sustainability, responsibility and ethics as foundational parameters. It's a new way to track innovation and generate cultural, societal and economic value.

You commented that "a product starts its life when it's released into the public domain and then it starts a narrative". Is the narrative equally as important as its conception, production and launch?

Actually, I wrote that in 2010 as part of my PhD research on the idea of Open Product, and it led to Open Product Licences which created a system of "Design by attribution". My thinking evolved from provocations Peter and I had developed for Platform 5 Design Products at the RCA back in 2001 on subjects such as "Death of a Product", where we went beyond recycling into multiple speculative afterlife product narratives - from kamikaze objects to fetishism. I developed the idea while working on a new programme for Design Entrepreneurship at Goldsmiths, where experienced designers were faced with a lack of systems for attribution for others to build upon their work.

"Do you want to be the next Lawrence Lessig?" is how I approached Alex Hamilton, who had been recognised as the "most innovative lawyer" by the FT. We proceeded to develop ideas for Open Product Licences, aided by lawyer friends who had won major corporate cases in the 3D electronic products domain and who were happy to contribute for beer money. Luckily for me, when we wanted to scale, Innovate UK (then TSB) recognised the value of pre-empting this space of new licensing and regulation and agreed to co-fund the process, and CERN supported us to build on their Open Hardware licences.This approach to developing product narratives through a chain of attributions has since become very influential. Both IP systems that we are building for the EU programmes and the Industry Commons concept for industrial data marketplaces support innovation to evolve in a trackable chain that logs the attribution and creates continuously evolving and sometimes forking narratives. These globally-relevant systems, which are causing quite a stir in some quarters since they affect the nature of trade and economy, owe their existence to a few beer rounds with brilliant people – as many good narratives do.

So much of your work and thought leadership focuses on bringing people together to make decisions for the future. What does it feel like to work together when you see the same potential in an idea or a product?

It's all about how you set the foundational rules for engagement. It means, for example, reframing how we think about inclusion. This is not about including several categories of people because as soon as you separate people into categories, you introduce bias in the data collection. Instead, we start by asking, "where do we converge?". It's about avoiding box-ticking and tokenism and instead looking at how we can discover every possible talent, beyond-human, beyond-Euro-centric. So a narrative develops from where we come together, over what issues. If you have this as a starting point, you have a very different atmosphere in the room from the beginning, people start on a different footing, and their minds focus on the task at hand or the challenge they're jointly facing. They embrace different perspectives as insightful and hugely inspiring towards a common mission. It feels great.

Being hands-on is also immensely stimulating. During the 2020-2021 pandemic, we focused on immersing our labs physically in the natural ecosystems that are under threat and very important for our social, cultural and natural living environments, such as some of the largest wetlands in Europe. In our official geographical orientation systems, they often appear minimal – for instance, the sea appears as a blue colour, or the living ecosystems are not marked at all. So we worked on various new types of markers to draw attention to those ecosystems, through sound signalling, by creating artificial life with neural networks, or by multidisciplinary collaborations between oceanographers, technologists and artists. The systems that we build and the mental models we project onto those systems can fundamentally alter our collective experience.

Taking on responsibility can also be immensely rewarding. We have proposed guidelines for a JUST data researcher. You may have heard of the idea of FAIR data, which is about creating fair data exchanges – Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. But then we have to add human responsibility. This is the responsibility of the researcher or data owner. JUST stands for Judicious, Unbiased, Safe and Transparent. It is not a metric because unbiased data doesn't exist – a data set may have been collected from a select group of people or in particular circumstances. We want data owners, citizen scientists and creators of data, to be conscious of how they collect or process that data, its context, its provenance, its bias, its safety in terms of privacy or sensitive information, and to annotate it for the next person. JUST data annotation acts as a memory aid for the fact that a data set will give you a particular viewpoint, but it does not actually create a universal truth. Data bias is quickly revealed when we work together on the ground, in the physical space. Most city governments still think of IoT systems in terms of service delivery, and few understand that connectivity now permeates all of the cultural spaces in between the nodes and synapses and that it allows for a high level of engagement and co-creation of experiences. In this context, the fairness and justice must be felt on the ground.

As Innovation Advisor to the European Commission what are some of the areas that are at the forefront?

I have been feeding policy directly from the results of grassroots creative experimentation for the past ten years. This has led to evidence-based policy that is not about collecting statistics but rather based on hands-on collaborations and the prototyping of ideas and solutions. It is action-oriented. NEB - the New European Bauhaus – places, for the first time, culture and design at the forefront of high-level policy towards the Green Deal. It aims to transfer best practice from grassroots experimentation on the ground directly to policy to inspire missions and, in turn, for policymakers to create mechanisms that further support activities on the ground, creating a virtuous cycle. The value of culture as a driver of behavioural change, inclusion and cohesion, and the value of creativity as central to all research and innovation is now very much integrated into the thinking of all EU funding mechanisms. Culture and creativity are now central to literally billions of Euros of investments as one of the key drivers of innovation and sustainability.

This wasn't always the case. In the past, the UK was well in front of the EU in terms of investing in culture and integrating creative industries in its political roadmaps. In the EU, I initially estimated it would take ten years for a paradigm shift. But things considerably sped up when all industry needed to urgently transition to data-driven systems - our experimentation was pointing to some clear clues for best practice in system design or to new interactions with frontier technologies, and our direction became more relevant for the main R&I agenda. For example, many of us reacted to the 2017 paradigm of Industry 4.0: Automation, with a human-centric approach. This was noted by industry and policymakers, and the paradigm was updated in 2021 to Industry 5.0: Human-centric. But now, with the New European Bauhaus movement, we are feeding policy directly at high level, and we have already shifted the paradigm to a more-than-human ecosystemic approach. Our ambitions towards greater industrial sustainability demand a fast paradigm and behavioural shift towards sustainable ecosystems – so if we are to continue with the version control, we can expect fast progression towards an Industry 6.0: Ecosystemic paradigm.

Has a Covid-19 world enhanced creativity and innovation?

Society's experience with the pandemic has highlighted the importance of culture for physical and mental health. But also, the changing technological conditions at work and affordances created by frontier technologies mean that we need to reframe several of our existing notions of what constitutes healthy human beings and healthy other beings, environments and ecosystems. Our prototyping environments have led on experiments with humans-in-the-loop, where the impact of frontier technologies – such as AI, deep learning and brain-computer interfaces – can be tested in safe environments, and challenges addressed before applications are deployed at scale.These experiments test the extent to which the technology enables or obstructs human agency, decision making processes and accountability. This dimension is directly linked to safeguarding health and wellbeing, including new data- and media-driven issues of privacy, bias and discrimination, physical distancing and isolation, and social media impact on mental health. So in this sense, we see culture and design as safeguarding the social and ethical dimension of technology.

You currently hold a number of different roles. How do you balance working on demanding and often difficult decisions concurrently?

One way of avoiding decision bottlenecks is to drop judgement or prejudice about different sectors' jargon which is there for very good reasons. Take policy acronyms, for example - they may sound obscure and incomprehensible. But if you are doing a good job in policy and you are well informed, you will understand that each one of these shortcuts contains information about a long and arduous process that has resulted in a valuable mission, and you optimise your communication by referring to it with an acronym - much like you would use a symbol or a logo. The worst thing you can do is approach ignorance of different domain activities with arrogance instead of asking the right questions and becoming well informed. So I learn the languages and modes of expression in these different environments - science, policy, research - and work on bridging, translating and opening doors. I am both a pragmatic optimist as well as able to bloody-mindedly dig my heels in to defend fairness and justice for the interests of the community. I am known for fending off prominent lawyers, big corporates and research cartels when they try and exploit or obliterate valuable community contributions. One of my pet projects is to design the antidote to the CIA/OSS 1944 "Simple Sabotage Field Manual", which is used regularly in bureaucratic processes, almost by the book, by those who wish to undermine initiatives. Another is to continue to design agile, decentralised systems that support decision-making so that the bottom of stale old processes will fall out. As I always say, following Dennis Gabor and Alan Kay, "We don't predict the future, we invent it".

You want to build better world. What do you think we need to do to achieve this?

I create "acupuncture points" that galvanise people around common missions. I find this important because we are creating the new railway tracks that everything will run on and affect how everything operates. This work is progressing very fast now with the Industry Commons. During our intense week-long experimentations, everyone is pushed to their limits. Those who progress past their usual breaking point suspend disbelief, build confidence and emerge on the other side with new realisations. Anybody sceptical or antagonistic is invited to join in, and I can guarantee you that their perception of what they're dealing with changes. We even place brilliant minds who are incredibly open, curious, willing to collaborate and experiment, outside their comfort zone. In our labs in Stockholm in 2018, we got 83 postgraduates, professors, people from industry, artists, accomplished and mature professionals who were part of a high-level lab to bounce their voices off the Moon via the Dwingeloo Radio Telescope in the North of the Netherlands, facilitated by artist Martine-Nicole Rojina. It took around 2.4 seconds for each voice to literally bounce off the surface of the Moon and then be returned into their ear. Of course, it's not a breakthrough in scientific terms. But it is part of a process and affects human experience - it places it in a completely different mental frame in terms of the perspective they can have on the world. They realise they can literally attempt moonshots. This is a very important element of our labs and leads to phenomenal results. Based on this, we can confidently say that, for us, the future of work is driven by missions. And this is something that I have rolled into the New European Bauhaus as an ambition.

Our satellites have also been growing. These are communities from various different countries who join remotely – usually postgraduate students in the middle of a really difficult project or experienced art+science research teams opening up new research directions. They absorb a wealth of inspiration that boosts their project development and their own personal development. This often results in long-term transnational collaborations. I always say that if every one of thousands of participants in this process is able to take one step forward in their personal development, no matter what their starting point or background, we will have a phenomenal social transformation as a result.