Key details

Date

- 26 November 2025

Read time

- 3 minutes

draught is a new online journal from the School of Arts and Humanities at the Royal College of Art, celebrating the creative in-between — the vulnerable, revealing space where ideas form before they’re finished

A new online journal dedicated to documenting the evolution of work before completion, called draught, has launched. As a counterpoint to the way creative output is typically celebrated — i.e. the unveiling of a finished piece — draught turns its attention to the liminal space in between; the fragile, forming stage. It is a place where many feel uncomfortable, even insufficient. But this journal seeks to honour the very act of making; the bravery required to take a pen to a blank page.

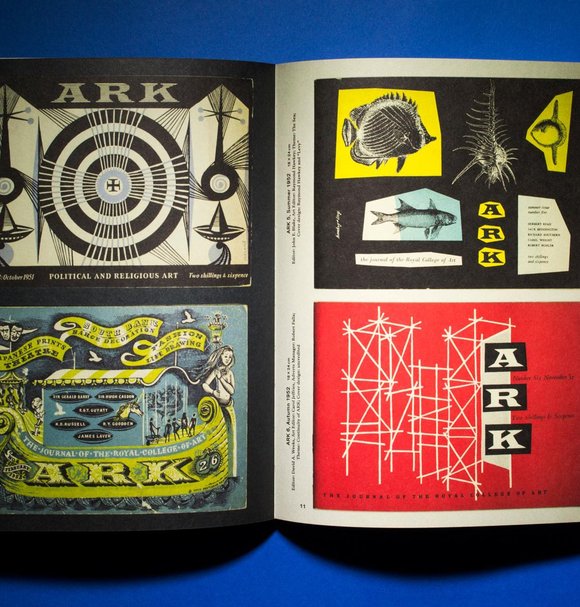

A collaboration between the RCA's School of Arts and Humanities and invited external contributors, the journal will publish twice a year, with shorter pieces added every six weeks. It includes feature articles, conversations, studio visits and portfolios, alongside recurring sections that focus on specific facets of creative work: detail, which examines one aspect of a piece with microscopic attention; I Wish I’d Made, which offers space to admire, even envy, the work of another; and adjacencies, in which two seemingly disparate works are considered in relation to one another.

For students, speaking openly about work-in-progress is familiar territory; it is the foundation of the tutorial. But this public form of vulnerability is less common among more established figures, who might typically reserve such candour for close friends or collaborators. Contributors to the first issue include writer and poet Daisy Lafarge, director and author Mark Cousins, and curator and writer Glenn Adamson, each of whom engages with the theme from a distinct angle.

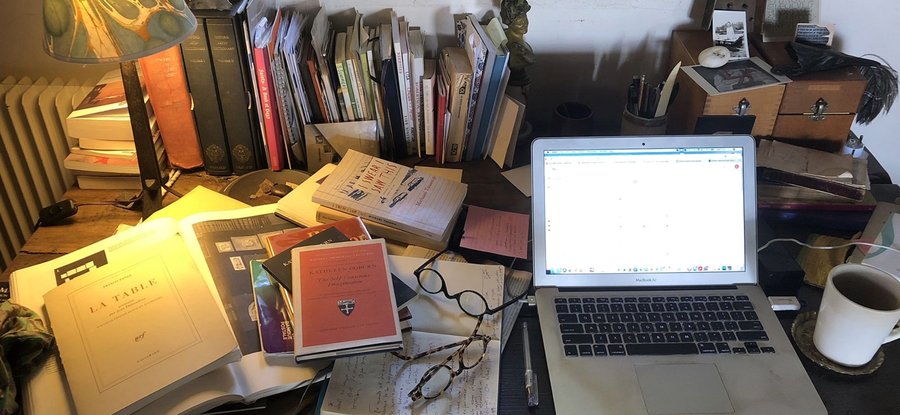

Studio visit with Rosalind Nashashibi as told by draught contributor Elena Narbutaitė

Studio visit with Rosalind Nashashibi as told by draught contributor Elena Narbutaitė

“There's something about the intimacy of it”, says co-creator and Head of Programme for the Writing MA, Jeremy Millar. “We have these conversations all the time — with students, with friends — where people open up in ways they never would in a formal interview when a book comes out or an exhibition happens. Part of what we're trying to do is share a bit of that space with people on the outside, and that requires a certain amount of trust because it is vulnerable.”

But draught does more than interrogate process; it also acknowledges the longing, the charged admiration that shadows creative practice. “In a pub or at a private view, people say that kind of thing all the time: ‘God, I wish I’d made that — such a great piece, I wish I’d thought of it,’” Millar says. “Those conversations aren’t unusual at all; what’s unusual is sharing them publicly.”

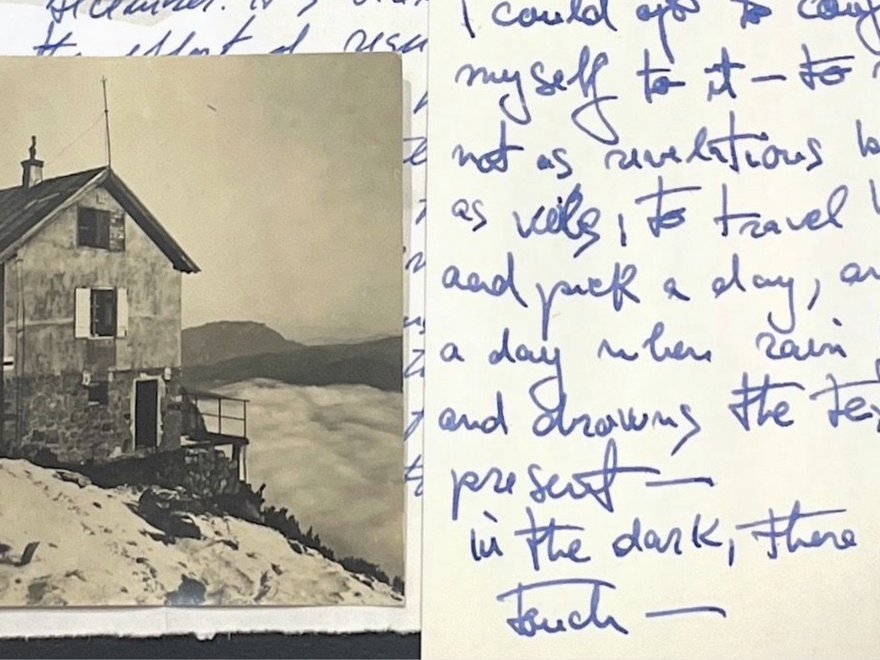

In her contribution to the I Wish I’d Made section, titled Being Joachim Meyerhoff, writer and translator Jen Calleja explores the strange magic of writing in the footsteps of a beloved author. Translation, she suggests, is a kind of apprenticeship; a temporary inhabiting of another creative mind. “Translating an author is like taking a 6–12 month intensive masterclass with them”, she says. “I suppose it's similar to an artist's apprentice learning to replicate a maestro's work. Translating so many writers has shown me that I can express myself through a variety of voices and styles, which is why all of my own books are so different.”

'On Bookmarks and Other Ruins', article for draught journal by Christina Tudor-Sideri

Mark Manders, - ( - / - / - / - / - ), 1998. Tea bags and offset print on paper, variable dimensions. Photo by Mark Manders.

Yet while Calleja is comfortable acknowledging the inspirations that feed her work, she is far less at ease with the open-endedness of an unfinished project. “I must finish or find closure — I hate being haunted by projects that never happened. Every piece of writing I've started, I've finished and found somewhere to publish it — it's just how I've always been.” She notes that translation projects defy this instinct: there are near-misses, stalled conversations, and instances of “ghosting” by initially enthusiastic publishers, an unfortunate truth of the industry that few writers are spared.

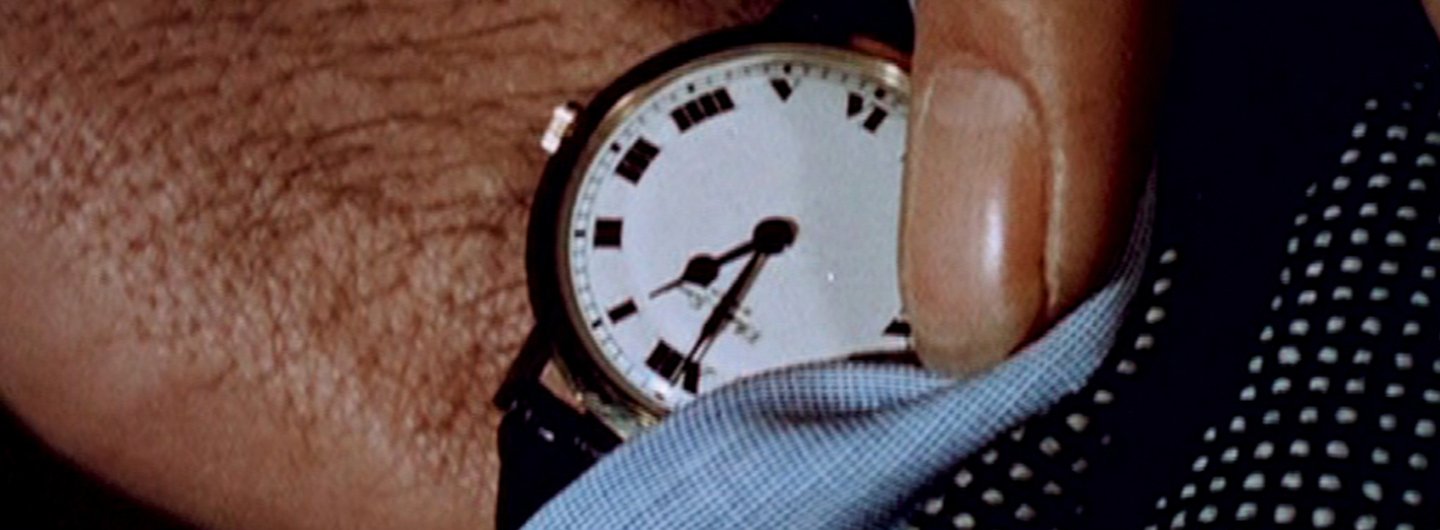

If unfinished conversations can falter, the connections forged through them nonetheless endure. Writing MA Associate Lecturer and managing editor of draught, Orit Gat, reflects on the unexpected dialogues that emerged as the first issue came together. “Watching the first issue take shape meant recognising how connections are made across the pages in surprising and beautiful ways”, she says. “There are reflections on the passage of time in the pieces by Daisy Lafarge, Francesca Wade and Lisa Robertson. They feel like they are in dialogue, even though none of the writers knew what the others were working on.” In this way, draught reveals that even in the unfinished, something whole can still take shape.