Key details

Date

- 7 February 2023

Read time

- 5 minutes

Yussef Agbo-Ola (Environmental Architecture, 2019) is the founder and creative director at Olaniyi Studio, London. This multidisciplinary architectural and artistic practice challenges the way that geological conditions and living ecosystems are experienced.

Key details

Date

- 7 February 2023

Read time

- 5 minutes

Often, the work of Olaniyi Studio takes the form of interactive experimental sensory environments, such as pavilions which have been created for exhibitions at the Serpentine Galleries in London and Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

Yussef spoke to us about his mission to expand environmental awareness through multidisciplinary projects and how studying Environmental Architecture at the RCA contributed to this journey.

“Olaniyi Studio constantly inspires me to re-interpret broader systems of knowledge and their environmental importance cross-culturally.”

Since leaving the RCA you’ve set up Olaniyi Studio. Could you tell us a bit about the studio?

Olaniyi Studio is an expanded form of my art practice. Its core mission is to expand environmental awareness through architectural design, immersive environmental art, photography, environmental contemplation temples, material science, experimental sound design, and conceptual writing.

Each series of Olaniyi Studio’s experiments focuses on depicting the multi-layered connections between an array of sensory environments across scales and disciplines: social, cultural, political, biological. Olaniyi Studio constantly inspires me to re-interpret broader systems of knowledge and their environmental importance cross-culturally.

Olaniyi Studio is simply inspired by entropy, the ephemeral and environmental empathy. The truth is that nothing is constant, everything transforms and is in a constant state of movement. This phenomenon has become the overarching design inspiration of the studio in regard to how we work on projects; peeling back each layer of an environmental system is at the foundation of what Olaniyi Studio creates.

“For me climate change is a reflection of an imbalance in our perceptual awareness or empathy for the environmental systems that we so dearly are connected to.”

![IKUM: Drying Temple, Back to Earth exhibition at Serpentine North [22 June - 18 September]](https://rca-media2.rca.ac.uk/images/_DSC0185.original.jpg)

You have worked on some exciting projects recently including creating environmental contemplation temples for the Serpentine Galleries and Palais de Tokyo. These projects engage visitors in a very bodily way, through the senses and a spatial experience. How did you arrive at this approach to exploring environmental issues and why do you think it is effective?

After spending time walking trails deep in the Amazon rainforest I realised that the forest presents us with many forms, colours, smells, and sounds that connect us to our ancestors and organisms all around us. It was through this meditative reflection that I felt a deep conviction to express this energy in my works.

‘Nono: Soil Temple’ is an architectural expression of this feeling. I wanted to translate this into a space that allows for an experience of the underground, a journey through the spiritual force of soil as a living architectural pavilion. Soil herself is the first living architecture. Her very chemistry of decayed organic matter and crushed stones creates an architectural relationship where her inhabitants – microorganisms – work in a symbiotic relationship with her so that life in the form of plants, animals, and humans can thrive.

For me climate change is a reflection of an imbalance in our perceptual awareness or empathy for the environmental systems that we so dearly are connected to. ‘Nono: Soil Temple’ questions this and is designed as a reflection on soil with soil. The temple is alive and through a sensory engagement with it the process of purification is initiated as a living architectural entity.

When one slows down and truly listens to a mountain, truly touches soil, truly sees a river, or truly smells a flower there is a magic that happens in our mental networks that induces environmental empathy. This connection through the senses is what these works try to recreate through poetic architectural design. This approach to design maps out a clear focus in the planning process, which is to formulate a spatial apparatus that allows for contemplation of the environmental unseen, or a reverence to the delicate fibres that hold dynamic ecosystems together through perceptual sensations.

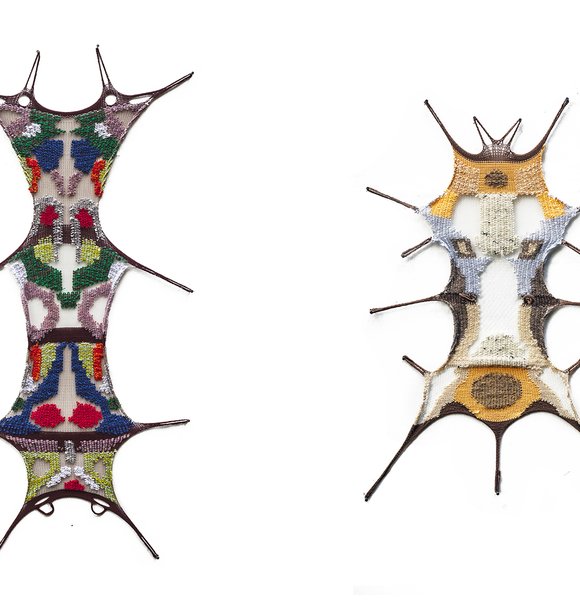

You recently made a series of shoes from diverse and unexpected natural materials including volcanic dust and cacao powder. What is the concept behind these shoes?

I have been experimenting and making plant based architectural materials at the studio for around eight years. Plant fibres mixed with clays, plant starch, and other organic additives make up the soles of the footwear. The upper has a different formula of materials and they react as if they were still plant skin in a living form, yet have new molecular properties of tension based on the natural additives that control their decay rate. These additives could be herbs, silica, flowers, pigment, bone fibre, sand, algae, pine sap and others.

![Olaniyi Studio Footwear. [KAJOLA] Collection: [FEx352.8]-[9oi]](https://rca-media2.rca.ac.uk/images/IMG_3828.original.jpg)

Each pattern is multi-layered with different plant skin properties to mimic the decay process of the forest. It is essential that some of the plant skin edges are left undone so that over time the material can crack and curl back on itself. This allows the shoe to design itself in collaboration with the weather.

We want the artworks to travel to different environments over time and slightly transform based on the environmental conditions of that area. The shoes are made of organic materials from all over the world, so having the collection evolve and decay in different places adds a poetic perspective to the entropic process which can be used as an environmental awareness tool through design. This poetic perspective to design is really essential to my work.

“The RCA is a super-dynamic environment. It’s a multidisciplinary, multicultural environment that fosters amazing creativity with teaching, rigour and experimental ways of thinking.”

How did studying at the RCA prepare you for setting up your own studio?

Throughout my academic career I’ve been interested in how to bring art and science together, while thinking about what the environment is in terms of perception, philosophy and anthropology. I came to the RCA because the architecture programmes provided lines of research that expanded my core belief about different ways of thinking about ecological systems and how we affect them.

The RCA is a super-dynamic environment. It’s a multidisciplinary, multicultural environment that fosters amazing creativity with teaching, rigour and experimental ways of thinking. It fostered an environment where I could expand my ideology, my understanding about art and design and architecture while giving me the space to think about scale in a totally different way.

This time at RCA helped to crystallise my interest in the unseen: the microscopic, micro-organisms, and the mental ecology resulting in me developing my own philosophy of environmental poetic design. This combination of a collaborative yet multidisciplinary environment and the agglomeration of concentrated research equipped me with a passion to continue such creative rigour and intensity, therefore it was only right to explore this passion further with establishing Olaniyi Studio.

“This time at RCA helped to crystallise my interest in the unseen: the microscopic, micro-organisms, and the mental ecology resulting in me developing my own philosophy of environmental poetic design.”

![Entropic Architecture Archive 980xi: "Contaminated Niger Delta H20 Sample [×9001nd]" -Mag10-5m.](https://rca-media2.rca.ac.uk/images/Screenshot_2022-01-05_at_kkkkkk.24_copy_copy.original.jpg)

Before coming to the RCA you did an anthropology degree at Virginia Commonwealth University, followed by an Art & Design BFA at Virginia State University and an MFA at Wimbledon College of Art. How did this mixed disciplinary background inform the work you did at the RCA?

I found myself oftentimes questioning why different cultures perceive the environment in different ways and how this then affects their design, homes and artefacts that are incorporated into their cultural belief systems. Poetic environmental architecture for me does not exist without a deep study of anthropological rituals, art and histories. For me it surpasses the political as a starting point for design. It’s impossible for me to separate either of these disciplines from each other and the more I learn within them, I see how they create the perfect chemistry for the work that my life is dedicated to at Olaniyi Studio.